The European honey bee (Apis mellifera) is often seen as a European immigrant to the Americas, having arrived aboard colonial ships around 1622. For centuries, we’ve assumed that honey bees were newcomers to this continent. But a remarkable fossil discovery in Nevada is rewriting that story—and reframing the way we understand honey bees and their place in North America.

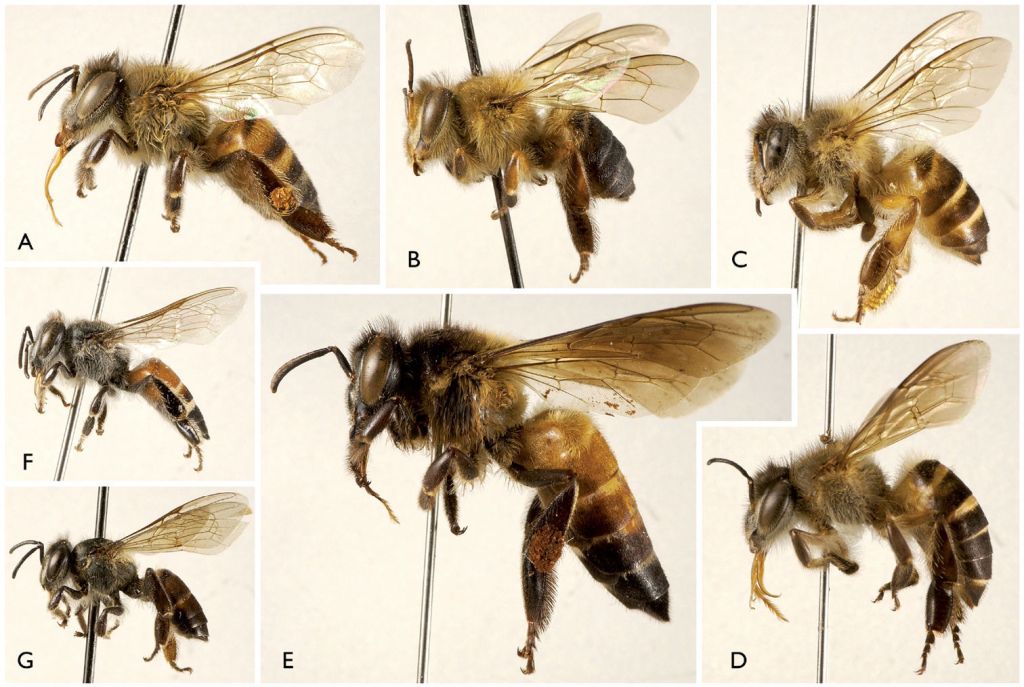

In 2009, paleontologists uncovered a single fossilized worker bee in the Stewart Valley Basin of west-central Nevada. This was no European honey bee. It was Apis nearctica, an extinct species of honey bee that lived during the middle Miocene epoch—14 million years ago. Preserved in a delicate paper shale deposit alongside other ancient insects, the fossil offers the first definitive evidence of honey bees native to North America.

It raises fascinating questions: How long did Apis nearctica persist here? What caused its extinction? And what role did it play in the ecosystems of prehistoric North America? These questions remain unanswered. But the fossil stands as a quiet reminder: honey bees once belonged to this land.

Apis and Its Global Family

Honey bees belong to the family Apidae, which includes bumblebees, carpenter bees, long-horned bees, and other familiar genera. The genus Apis, which includes all true honey bees, has existed for over 60 million years. Today, seven species of honey bees are recognized:

- A. dorsata – Giant honey bee

- A. florea – Little honey bee

- A. cerana – Eastern honey bee

- A. mellifera – European or Western honey bee

- A. koschevnikovi – Koschevnikov’s bee

- A. nigrocincta – Philippine honey bee

- A. andreniformis – Black dwarf honey bee

All but A. mellifera are native to tropical or subtropical regions of South and Southeast Asia. Of the seven, Apis mellifera is the only species that has been widely domesticated and is now found across the globe—well beyond its native range.

Apis mellifera: A Global Citizen

Apis mellifera is the honey bee most beekeepers are familiar with—prized for its ability to produce honey, beeswax, and pollinate crops. This species includes 24 subspecies or “geographic races,” comparable to breeds of dogs. Italian (A. mellifera ligustica), Russian, Carniolan, Cordovan, and Africanized bees are among the most well-known.

Each race has its own temperament and adaptation. Italian bees are famously docile. Africanized bees, by contrast, are known for their defensiveness and rapid colony expansion.

Unlike its tropical cousins, Apis mellifera is uniquely adapted to temperate climates. It is the only species of honey-producing bee capable of thriving outside the tropics—a trait that has made it indispensable to agriculture across the Northern Hemisphere.

Ancient Honey, Without Honey Bees?

If honey bees didn’t return to North America until the 1600s, how did the Maya harvest honey long before that?

The answer lies in a different lineage of bees entirely: stingless bees of the tribe Meliponini. These bees, especially those in the genus Melipona, are native to the tropics and subtropics. Revered by the ancient Maya, stingless bees were more than pollinators—they were spiritual symbols. The Mayan bee god, Ah Muzen Cab, was honored for the gift of honey.

The Maya’s favorite stingless bee was Melipona beecheii, or kolil kab in Yucatec Maya, meaning “royal lady.” Unlike the vast colonies of honey bees, Melipona beecheii lives in smaller colonies and produces just two liters of honey per year—a fraction of the five gallons a typical honey bee hive can yield.

Families traditionally kept hives in hollow logs near their homes. But the spread of aggressive Africanized honey bees has threatened this ancient practice, as stingless bees are unable to compete for resources.

Melipona: Native Royalty of the Tropics

Stingless bees are found only in equatorial regions, and they are intimately tied to the flowers of their local habitats. Some species are smaller than fruit flies; others rival honey bees in size. Their diversity is remarkable—over 500 species—and their ecological roles are no less critical.

One striking example of co-evolution is the vanilla orchid, which relies on specific Melipona bees for pollination. Outside their native habitats, these orchids must be hand-pollinated—a task once performed by nature alone.

Echoes of Extinction and Return

The story of Apis mellifera in North America is often framed as an introduction. But if we consider the fossil evidence of Apis nearctica, perhaps it is better understood as a return. Like the horse—another species that evolved in North America, went extinct, and was reintroduced centuries later—Apis mellifera may be coming home to a land once pollinated by its ancient kin.

The next time someone says, “Honey bees aren’t native,” you might pause and reply:

“Not anymore. But they once were.”

References

-

Engel, M.S., Hinojosa, I.A., & Rasnitsyn, A.P. (2009). A honey bee from the Miocene of Nevada and the biogeography of Apis (Hymenoptera: Apidae: Apini). Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, 60.

-

Hrncir, M., Jarau, S., & Barth, F.G. (2016). Stingless bees (Meliponini): Senses and behavior. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 202(9-10), 597.

-

The Hive and the Honey Bee. (2010). Dadant & Sons. Pages 23–71.

5 responses to “Honey Bees in America: Native Origins and Modern Return”

[…] Read full article here: Native North American Honey Bees? — Native Beeology […]

[…] is evidence that honey bees existed in the Americas millions of years ago, but they went extinct. The adorable bumblers that make our honey today are relative […]

[…] Native Beeology. Native North American Honey Bees? https://nativebeeology.com/2018/01/26/native-honey-bees/ […]

Well written. Thank you for your time and information. The part about a bee that only pollinate’s the vanilla orchids, leaves me wondering if their specific honey has any distinctive flavor for the better or worse? I would love any information on this I can get. Thank you

[…] fly,” and thought it associated with European settlements. While North America once had its own native species of honeybees, they went extinct long before the European honeybee made American landfall in the […]